It’s no wonder that fiddles are so often compared to women. Fiddles are feminine. French horns, kettledrums? They’re masculine. I’m speaking now from the male point of view, the only POV I’m familiar with.

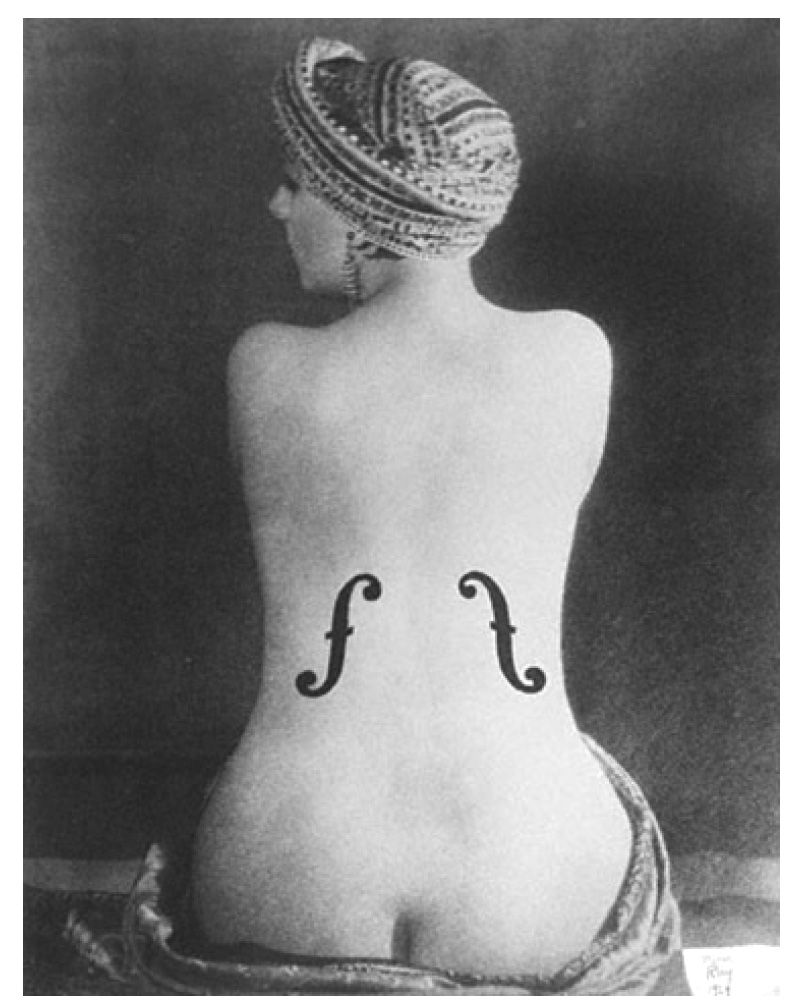

Fiddles are definitely of the feminine gender. Just look at their shapes. There are the obvious curves, the long neck, like a Mondrian painting. But more than that, beyond the obvious, is the feeling of embrace, the need to coax, and the pleasure of response. The American surrealist, Man Ray saw it in the early 1920s with his classic photograph, Le Violon d’Ingres.

Often, like female encounters, fiddle encounters can happen when you least expect them. Some bit of serendipity, best pondered later in life, will altered the entire course of your existence, throwing you into another orbit, née a whole new galaxy. Chance encounters of the finest kind.

Like a time past, when I chanced past a music store and stopped in. Premonition perhaps?

It was one of those intriguing old high ceiling storefronts with the door set back from the street, and windows on either side displaying any manner of song books, harmonicas, kazoos and used instruments. Just enough related ephemera to pique the curiosity and warrant a stop. The storefront sported a long narrow sign over the windows that read, “Folk Music.” Not really needing anything, save perhaps a manuscript book, I took that as reason enough to venture in. I surveyed the premises, noted with passing interest the abundance of old, used, and definitely folk-issue instruments. I made my way to the sheet music rack, and after a bit of browsing, found a nicely bound manuscript book blank with possibilities, a profusion of empty staves ripe for inspiration.

Heading for the checkout counter, I was distracted momentarily by the glint and shine of new varnish hanging on the wall. Tucked in amongst the old instruments, a fiddle. It was all together too new, too bright, and lacking any of the well-worn marks of age so often associated with the acoustic maturity of older instruments. But still – and not unlike the aforementioned comely young maiden of the tattoo – it was, in its own way, compelling. On further examination the nicely shaped one-piece back – again, not unlike the aforementioned comely young maiden of the tattoo – was enough in itself to push me to the edge of purchase or barter, The heft of the instrument was right, not too heavy, good balance, nicely figured wood, the work of a craftsman. But did it have a voice?

“Silver Threads Among The Gold” seemed an appropriate choice of melody, and when finally I was able to draw a bow across the strings, the tone matched the look. Bold, strong, lively, warm, yet still a bit untested, crying out to be played. Predictably, it was love at first sight. As I recall, a bit of cash and a banjo in part trade finally did the deal. The label read “Conrad Goetz, 1972. Model No. 30,” featuring the maker’s mark as well as a brand inside the back. Not that labels mean all that much, but at least this one had some Pedigree.

Violin labels have always been suspect, and a good appraiser never looks there first. Before copyright laws, thousands of student fiddles have been sold over the years bearing famous labels. Stradivarius, working in the 1600s would have needed six sets of hands and a hundred years of 40-hour days to produce that many originals in his native Italian shop. And he never worked in “Czechoslovakia, ca.1925,” as a good number of labels have proudly proclaimed over the years.

Mr. Goetz’s 1972 Model No. 30 improved with use. The wood, they say, begins to respond to the vibrations and resonate to the tones produced. It was a fine instrument and one I took great care of, with the possible exception of the time I smashed it against a wall. But that’s another story, which I probably should tell now.

It happened during a summer music workshop in front of 20 or 30 students, all eager to learn new tunes and techniques. Sitting in front of the group, their tape recorders in the pause mode, I rambled on incessantly, absentmindedly twirling my fiddle in my left hand – a habit mysteriously acquired, and hard to shake – when out of the blue, in a startling moment of poltergeist, the fiddle leapt from my hand, flew in a lazy, slow-motion arc, which, I’m sure, in real time took only seconds, impacted solidly against the wall and exploded into a number of separate pieces. The neck popped off the body, the pegs flew out of the scroll, and the tackle – strings, bridge, and tailpiece – went flying as well.

Now, not wanting to upset the group too much, and attempting to maintain my scholarly composure, I simply looked up and said, “Can I use someone else’s fiddle?” at which point several of the students got up and left.

The fiddle came apart in clean and repairable pieces, and fortunately there was a resident luthier present who glued the whole thing back together overnight. Miraculously, there wasn’t as much as a scratch or crack on the instrument.

I’ve since moved on to other alluring fiddles. Remembering them all is like reading the names on a war memorial: Antonio Stradivarius, Czechoslovakia, 1920; George Craske, Manchester & London, 1864; George Gemunder, New York, 1885, Joseph Rocca , Turin, 1861, Goffredo Cappa, Saluzza, Italy, ca.1700; Conrad Goetz, Marcknikirken, 1972; Terence O’Laughlin, Boston, 1917; Joseph Rockwell, Stoughton, MA, 1880; Martha Hassett, Boston, 1992; Heinrich Th. Heberlein jr. Markneukirchen 1909. And most recently, the newest, Jacob Brillhart, Chelsea, VT, 2021.

I once knew an old fiddler who was a pool hustler. He didn’t carry a custom cue, but always, “played off the wall.” That was his gimmick. Claimed it threw off the competition. “You see,” he once told me, “If you know what you’re doing, you can play with any old stick.”

It’s said that the classic American violinist Fritz Kreitzler –- following the accusations of a New York critic who claimed his fine tone was merely the result of owning a rare Stradivarius – once came on stage at Carnegie Hall, brought tears to the eyes with a stunning rendition of “Schon Rosmarin,” then smashed his fiddle against the piano and walked off stage. It was, in fact, an inexpensive student copy of a Strad. If you know what you’re doing…

Somehow, these kinds of stories just lend credence to the notion that one violin is not enough. As a player I’m always searching for that perfect instrument. Not necessarily the “Strad-in-the-attic” sort of thing, but a sleeper, the unexpected. A chance encounter of the finest kind.